Time is our most precious resource, yet most of us fail to realise that when we get sucked into a pile of seemingly endless activities. A popular approach to tackle this dilemma is aiming to optimise one’s time management capabilities. The common theme is to squeeze in a plethora of tasks into one’s calendar, whilst focussing to complete them as effectively as possible.

Oliver Burkeman suggest a refreshing alternative to the way we currently conceptualise and value our time. His philosophical take on time management reveals deep wisdom from ancient thinkers, researchers and spiritual figures. Here are my favourite lessons which I dissected from the book.

The title ‘Four Thousand Weeks’ refers to the average lifespan of a human in western society – roughly amounting to 80 years. Realising this unshakable truth, triggers different kinds of emotions in people. Many of which crystallise in a form of anxiety when confronted with the unavoidability of life’s finitude. Consequentially, it shouldn’t come to any surprise why many of us are striving to put our limited time to the ‘best’ use possible. However, not too long ago, human’s used to perceive time very differently.

People weren’t trying to optimise their time until it was treated as a resource rather than an inherent part of life.

During medieval times, most people worked regular agriculture or craftsman jobs. Time still played a role back then but was perceived in a completely different way. One’s waking hours were influenced by dawn and sunset, whereas one’s working schedule was tied to the sowing and harvesting seasons. Time wasn’t something that had to be neatly organised and optimised but was rather viewed as an intrinsic part of life – marked by seasons and daylight hours.

With the rise of the industrial revolution in the late 18th century when this concept started to take a stark shift. With the introduction of factories, time became a resource that could be scaled for efficiency and is the core premise for all time wrangles that we experience today. Once we start treating time as a resource, it’s completely human to feel inclined to use it wisely and avoid wasting it. This concept carries over into other domains such as spending one’s off-time well which brings us to the next point.

If work is the purpose of existence, leisure becomes an opportunity to recharge and replenishment one’s capability to merely accomplish more work.

The attitude which we hold towards leisure today would seem totally absurd to someone living before the industrial revolution. Leisure wasn’t seen as a means to an end but rather the contrary. According to Aristotle, leisure was one of the highest virtues because it was chosen for its own sake compared to other qualities like bravery or nobility which were pursued for status or financial reasons.

In contrast, the contemporary understanding of leisure revolves around using off-time to recuperate and replenish one’s energy to ultimately complete further work. This world-view promotes a bizarre concept for well spent days off, in which anything that doesn’t create some form of value is seen as mere laziness.

In addition, this model of thought ignores the fundamental aspect that it’s humanly impossible to achieve everything in one lifetime. By choosing to do something, one consequentially sacrifices all the other opportunities which could have been done at that moment.

The focus of time management shouldn’t be to unrealistically presume that everything will be done, but to deliberately decide what not to do whilst accepting one’s finitude.

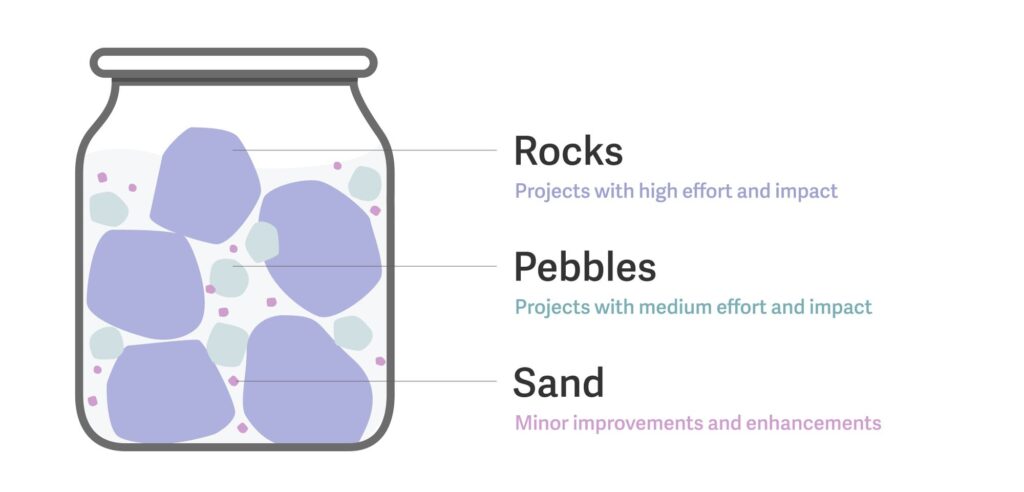

According to Burkeman, most time management maxims miss the point of considering the reality of finitude. He thereby refers to the famous ‘rocks, pebbles and sand’ analogy by Steven Covey. As the name suggests, you have these three resources, which metaphorically stand for the different levels of priorities in our lives. He then tasks the audience to fit all the items into the jar.

Covey solves this problem by fitting the rocks in first (biggest priorities), followed by the pebbles (medium priorities) and lastly the sand (lowest priorities). The moral of the thought experiment is that you couldn’t fill the jar by reversing the order because the pebbles and sand fill the gaps which the rocks left behind.

Burkeman’s main gripe with the analogy is the fact that it presupposes that there is enough room in the jar to fit all our priorities in the first place. The only thing one seemingly has to do, is picking the right order. However, what if the main problem is not the order of our priorities, but the fact that our lives aren’t big enough to hold everything of importance to us?

Accepting the limitations of reality and letting go of the phantasy that everything can be done is the only way to achieve psychological freedom. Instead, one should focus on a limited number of personal aspirations and make them count. You have to choose a few things, sacrifice everything else, and deal with the inevitable sense of loss that results.

Missing out on opportunities in order to pursue what’s important to us is what makes our choices meaningful in the first place. Instead of having FOMO of dropping an opportunity, Burkeman suggests adopting a JOMO (Joy Of Missing Out) mindset:

JOMO: “The thrilling recognition that you wouldn’t even really want to be able to do everything, since if you didn’t have to decide what to miss out on, your choices couldn’t truly mean anything.”

This rational ties in with the feeling of procrastination, which we all struggle with to some extent. The point here is not to attempt to eradicate all procrastination, but to wisely choose what to procrastinate on in order to focus on what matters most. The real benchmark of any time management technique should be whether it helps you to neglect the right things.

If you tried to find time for your most important activity be dealing with the less important activities first, you’ll end up with no time for your top priority. So if a specific activity truly matters to you, the only way to ensure it will happen is to do at least some of it today!

Leave a Reply